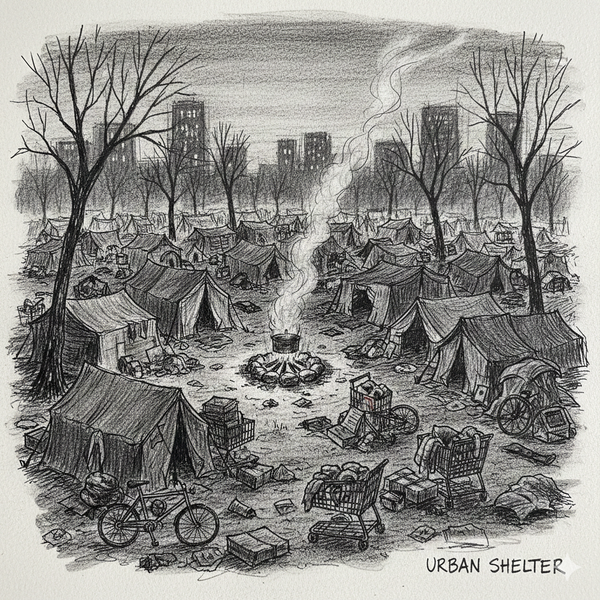

Christmas Eve and the People We Keep Out in the Cold

Chelsea Lynn December 24, 2025

It’s Christmas Eve in Lansing. Lights glitter across the streets. Families gather around tables. Holiday music fills the air. Meanwhile, the Fallen Angels encampment—a community some residents had called home for months—has been cleared. Reporters say dozens of residents were relocated into temporary hotel housing under a court order as of December 22. City officials framed the move as necessary for safety. Winter is dangerous: fires, frostbite, carbon monoxide exposure. A Code Blue was declared, warming centers were opened, and six weeks of hotel placement were provided. But the shelters and hotel placement have limits. They often prohibit pets. They separate couples. They offer chairs, not beds. And after six weeks, permanent housing is not guaranteed. What was intended as temporary refuge feels more like a thank-you note for leaving. Every December, the same pattern repeats. Encampments that grew visible during winter are cleared—not because homelessness has been solved—but because it is inconvenient to have people living in public view. Displacement moves people from one dangerous environment to another, often more isolated and less visible, increasing the risk of overdose, fire, or hypothermia. City leaders argue they acted in the name of public safety and sanitation. Downtown businesses reported vandalism, theft, and human waste. These concerns are real. People who live and work downtown deserve safe public spaces. But so do the unhoused—especially in winter. Relocation without a long-term plan does not protect lives; it exposes people to new risks. The homelessness crisis is structural. Michigan is short tens of thousands of affordable housing units. Rents have risen sharply. Shelters are underfunded. People are one crisis away from losing everything. And yet, when they create a community in public spaces, they are eventually forced to move—timed for the holidays, with temporary shelter that has an expiration date, and no guarantee of stability. This is not a call for permanent, unregulated encampments. It is a call for real solutions: low-barrier shelter beds, sanctioned camping with heat and bathrooms, housing programs with permanent placements, and investment in affordable housing. Dignity must come first; displacement should come last. On this Christmas Eve, when warmth and togetherness are celebrated, let us remember the people who were asked to leave, who now must navigate winter with no guarantee of shelter beyond six weeks. Let us not cheer that the encampment is gone. Let us question why its disappearance feels like an ending when it should have been a beginning. We can do better. We must do better.