Lansing Keeps Managing Homelessness — and That’s the Problem

By Chelsea Lynn

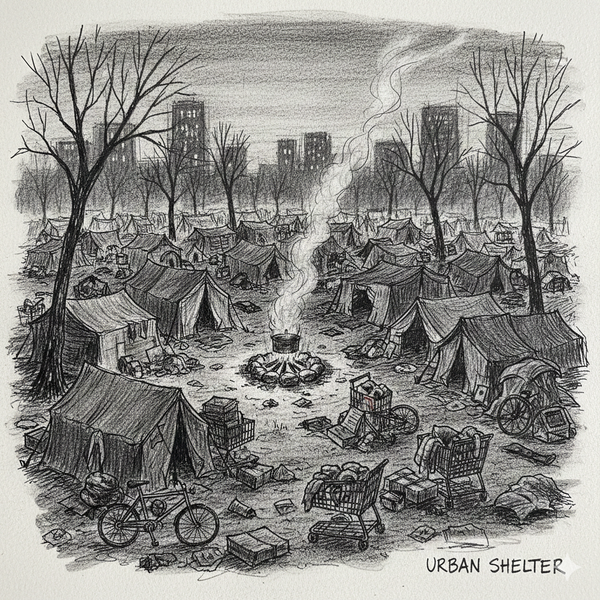

December 17, 2025 Lansing does not lack compassion. It lacks follow‑through. That became clear in September, when city officials, law enforcement, and members of the media walked through the Dietrich Park encampment with cameras in tow. The visit was framed as concern for public health and safety. But for many residents and advocates, the moment was symbolic not because it was dramatic — but because it reflected what Lansing’s own data shows: the city responds quickly to homelessness, but rarely resolves it. According to the City of Lansing’s 2025 homelessness study, more than 75 percent of unhoused residents who enter the system are connected to emergency shelter or stabilization services. That sounds like success — until you look at what happens next. Only about 12 percent transition into permanent housing. Emergency response without permanent exits is not a solution. It is a holding pattern. More people enter the system each year than leave it. The result is a bottleneck that pushes people from shelter to encampment, from encampment to enforcement, and back again. This is not a failure of individuals. It is a failure of design. Nowhere is that failure clearer than in the data on families. Families with children make up approximately 41 percent of Lansing’s unhoused population — far higher than the national average. Yet families are less likely to receive direct support through the homelessness services system. Instead, they are often steered toward mainstream rental assistance or informal networks and are more likely to exit homelessness without coordinated help at all. When a homelessness system fails families, it is not malfunctioning — it is misdesigned. The same disconnect appears in discussions of equity. Administrative data shows that Black residents and other people of color access services and exit to housing at rates similar to the general population. But numbers alone capture access, not experience. Service providers and people with lived experience consistently describe discriminatory treatment, unequal enforcement, and environments that feel unsafe or unwelcoming. LGBTQIA+ residents, in particular, report avoiding congregate shelters because of safety concerns or inflexible rules, especially in religiously affiliated facilities. When people avoid services to protect their dignity or safety, they are often labeled “noncompliant.” The data may record neutrality. Lived experience records harm. Shelter access itself is uneven. Only about half of transitional‑aged youth use shelters. Older adults and chronically unhoused individuals fare better — but still not universally. People with medical needs or disabilities frequently encounter facilities that cannot accommodate them. Nearly half of unhoused residents report being turned away from shelters due to capacity limits, sometimes facing waitlists measured in months. When shelter space is unavailable, encampments become a survival strategy — not a preference. Yet enforcement continues even when no viable alternative exists. Lansing’s lack of a coordinated regional homelessness strategy compounds the problem. Not all providers participate in shared data systems. Follow‑up and aftercare support are limited. Many people lose housing shortly after placement and cycle back into homelessness, restarting the process from the beginning. This brings the conversation back to optics. Photography and reporting in public spaces are legal. But legality is not the same as legitimacy. When tents function as people’s homes, entering or filming those spaces without notice raises ethical questions about consent, dignity, and power — questions that law alone cannot answer. Visibility is not the same as accountability. In December, the city announced a settlement related to the Dietrich Park encampment that will provide temporary emergency shelter for up to six weeks, along with transportation. The move is necessary for winter safety. But temporary shelter addresses weather. Permanent housing addresses homelessness. Lansing continues to treat the former as a substitute for the latter. Research across the country consistently shows what works: permanent supportive housing, non‑congregate shelter options such as tiny homes or modular pods, targeted services for families and vulnerable populations, and strong aftercare support. These approaches reduce homelessness more effectively — and often more affordably — than repeated displacement. Lansing has the data. Lansing has the evidence. What remains is a policy choice. The city’s homelessness crisis is not a failure of compassion. It is a failure of design. And design, unlike fate, can be changed.